Pr Eric Souied 🇬🇧

The Pathologies

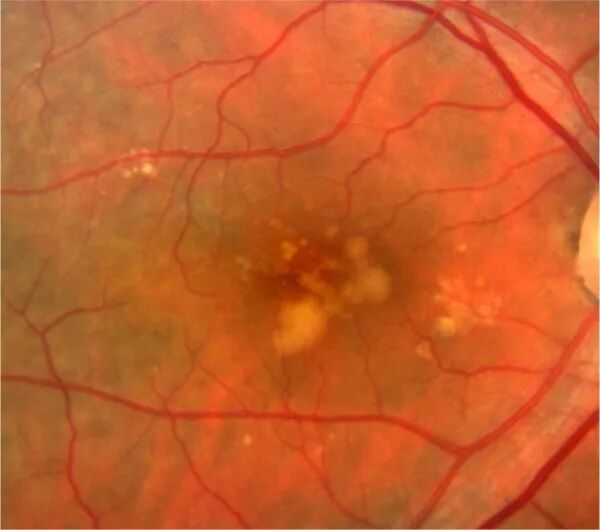

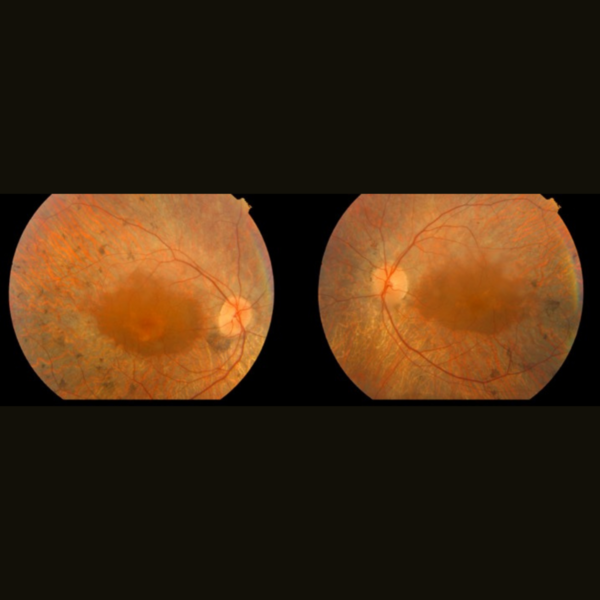

Age-Related Maculopathy

Age-Related Maculopathy

The macula is a small area, 2 mm2, located at the back of the eye, in the center of the retina. It is responsible for central vision, allowing us to see objects with precision and perceive colors. Several conditions can damage the macula, especially with age, leading to irreversible deterioration.

Age-related maculopathy (ARM) represents the early stage of macular aging. It is often asymptomatic in terms of visual symptoms.

ARM is characterized by the presence of alterations in the retinal pigment epithelium and/or retinal deposits called drusen in the macula. Having ARM in one or both eyes increases the risk of developing advanced ARM within 5 years, with a risk as high as 50%. Depending on the stage of ARM, preventive treatments with antioxidants may be prescribed.

It is crucial to detect the onset of ARM as early as possible through visual exams starting at the age of 50. Some factors can accelerate the progression to macular degeneration, such as smoking, obesity, or a family history. Conversely, a diet rich in long-chain omega-3 (DHA) and lutein (a carotenoid) can slow down the progression to advanced AMD.

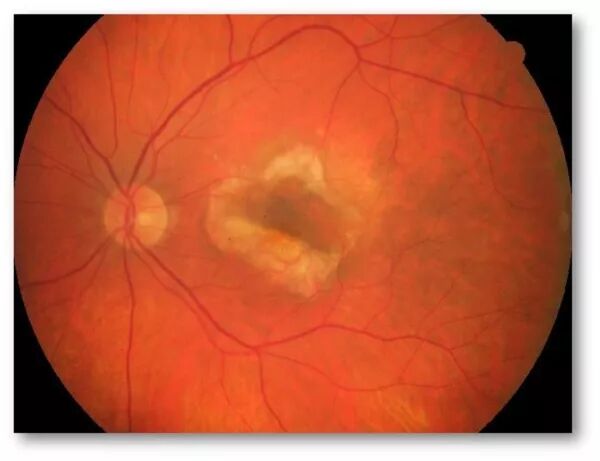

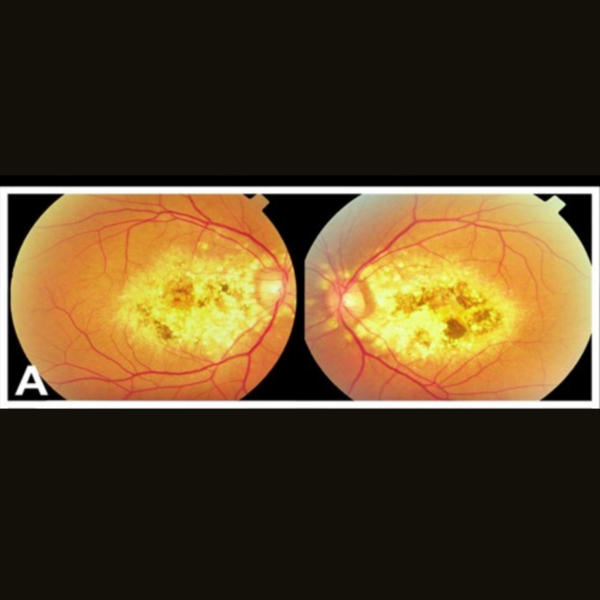

AMD

AMD

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common eye condition that primarily affects individuals over the age of fifty. It damages the macula irreversibly.

Clinical Sign: The initial clinical signs of ARMD include distortions of lines, known as metamorphopsia, and the appearance of a central spot, referred to as a scotoma.

Seek Urgent Consultation: see Doctolib

This condition causes blurry or lost central vision, with significant implications for many everyday tasks such as reading and driving. It is estimated that the disease currently affects over a million French people.

AMD manifests in two forms:

- Atrophic or dry form (more common, characterized by thinning of the retina). It results from the progressive atrophy of the layers of the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors. The visual impact is noticeable, but this process is slowly progressive over several months and years.

- Exudative or wet form (less common, characterized by abnormal blood vessel growth). The development of choroidal neovascularization in the macula leads to intra or subretinal edema, or retinal hemorrhages. Its progression is often rapid, evolving over a few weeks.

- Mixed forms can also exist. In these forms, atrophy and neovascularization coexist."

Professor Eric Souied is internationally recognized as one of the leading experts in AMD. In 1998, during his Ph.D. in Human Genetics, he identified the first genetic polymorphism involved in AMD

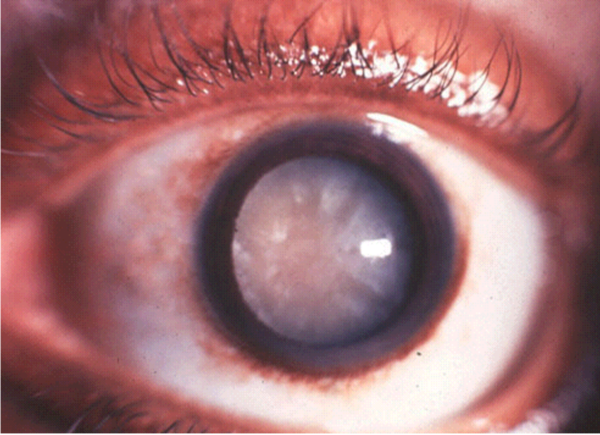

Cataract

Cataract

Cataract is a progressive clouding of the lens, the eye's natural lens, which is normally clear and transparent. With age, the structure of the lens changes, and its transparency decreases. Vision deteriorates both up close and far away and cannot be corrected with glasses.

Common symptoms include blurred vision, increased sensitivity to light, and reduced night vision. Cataracts are usually age-related, but they can also be caused by injuries, certain diseases, or as a result of taking certain medications. They can also be present from birth in certain specific cases.

The clouding of the lens leads to a decrease in vision, which can vary in severity. When the discomfort becomes too significant, the treatment involves a surgical procedure to replace the cloudy lens with an artificial lens.

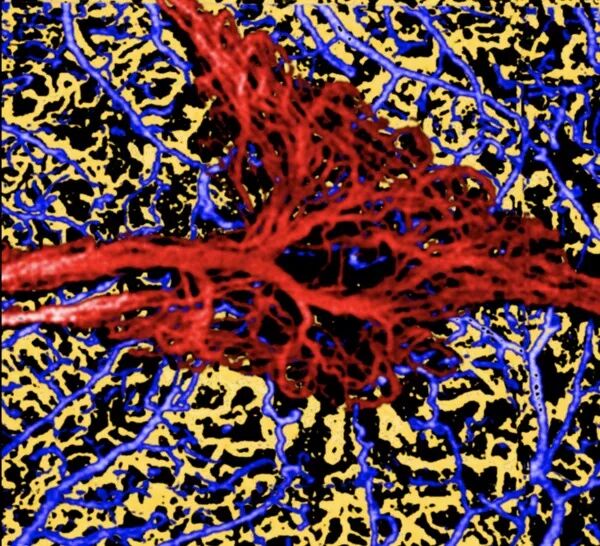

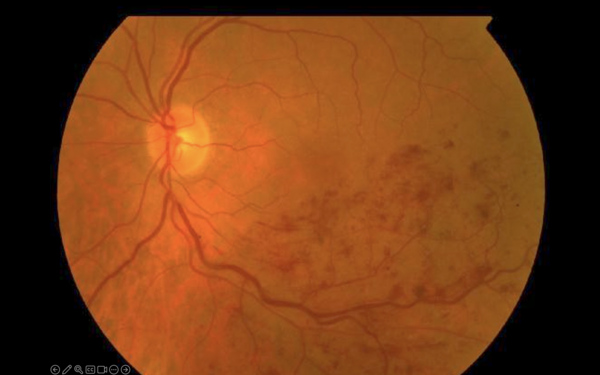

Rétinopathie diabétique

Rétinopathie diabétique

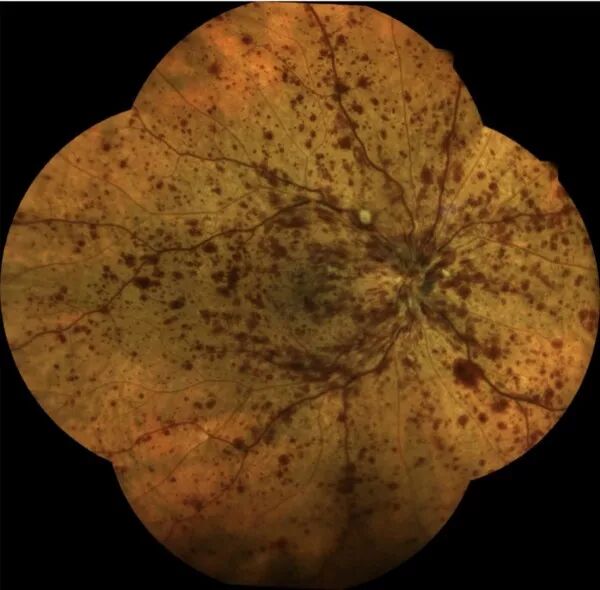

Diabetes is a disease that causes chronic hyperglycemia (an abnormal increase in blood sugar levels). This hyperglycemia leads to repeated inflammation of the retinal capillaries, resulting in their occlusion.

Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication of diabetes. It affects 50 to 80% of people who have had type 1 or type 2 diabetes for 20 years or more. It is, therefore, important for these individuals to have their vision regularly checked to detect and treat this condition as early as possible. Fundus examination should be done as soon as diabetes is diagnosed, and then at least once a year.

Diabetic retinopathy causes irreversible damage to the retina. It is one of the leading causes of blindness in developed countries.

Capillary occlusion leads to what is known as retinal ischemia, which means insufficient blood supply to the retina. There are two types of diabetic retinopathy: early diabetic retinopathy and advanced diabetic retinopathy. The most common form is non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), during which new blood vessels form abnormally. Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy can be minimal, moderate, or severe, with the presence of microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and dilated veins.

When retinal ischemia is significant, it becomes a trigger for neovascularization, meaning the formation of abnormal vessels within the retina. These neovessels are dangerous because they can lead to bleeding, retinal detachment, and even neovascular glaucoma. These complications are serious as they can result in blindness. Diabetic retinopathy can progress to a more severe form known as proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Diabetic retinopathy can lead to the formation of abnormal blood vessels that extend from the retina and block the outflow of fluid from the eye. It can also cause intraocular bleeding, the formation of scars at the back of the eye, or even retinal detachment.

Diabetes can also result in alterations in the macula. The macula is the central part of the retina, responsible for sharp vision. In the macular area, diabetes can lead to an abnormal accumulation of fluid, known as macular edema, which results in a decrease in vision.

The treatment of diabetic retinopathy aims to combat the damage caused to the retinal blood vessels by high levels of blood sugar. These vessels can swell and leak, or they can close, preventing blood from circulating properly. Sometimes, abnormal new blood vessels form on the retina.

Hereditary Macular and Retinal Dystrophies

Hereditary Macular and Retinal Dystrophies

Hereditary dystrophies represent a group of heterogeneous conditions, found with an approximate frequency of 1 in 3,500 individuals in the French population, affecting approximately 40,000 patients in France. These are considered 'rare' diseases, and their diagnosis is sometimes presumed or uncertain.

In 1994, Eric Souied published the first mutations in retinitis pigmentosa in France, in the Rhodospin gene and subsequently in the RDS and ROM1 genes.

Hereditary retinal dystrophies affect the entire retinal tissue. In addition to retinitis pigmentosa, many hereditary retinal conditions fall within the scope of this consultation, such as choroideremia, gyrate atrophy, ocular albinism, as well as mitochondrial or metabolic diseases.

Hereditary macular dystrophies exclusively or preferentially affect macular tissue. This is also a highly heterogeneous group of conditions, including Stargardt macular dystrophy, fundus flavimaculatus, Best macular dystrophy, adult-onset vitelliform dystrophy, cone dystrophies, reticular dystrophies, Sorsby macular dystrophy, X-linked retinoschisis, and drusen in young individuals.

A comprehensive assessment based on morphological and functional examinations will help distinguish between these different conditions

Myopic Maculopathy

Myopic Maculopathy

Myopia is defined by an eyeball that is longer than normal, requiring optical correction (measured in diopters) for distance vision to focus the image on the retina.

Complications of High Myopia:

High myopia is defined as myopia greater than 8 diopters; it represents a complex condition and can lead to numerous complications.

At the macular level, high myopia can be complicated by choroidal neovascularization, atrophy, Bruch's membrane rupture, retinoschisis, or macular hole.

High myopia can also be complicated by glaucoma, which is generally more severe than in the general population. Finally, high myopia can be complicated by cataracts, which occur earlier than in the general population.

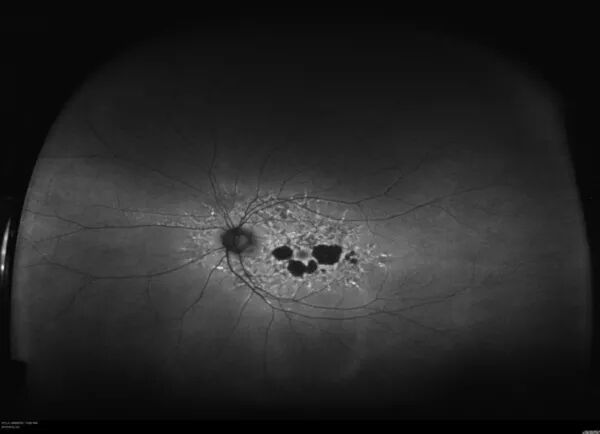

Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)

Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)

Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO) is the result of a sudden slowdown in blood circulation in the veins of the retina, which can have an impact on the overall blood flow in the retina, particularly upstream, affecting the circulation of blood in the retinal capillaries and arterioles. This disruption in retinal oxygenation can lead to varying degrees of visual disturbances.

RVO can be classified into two main types:

- Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO): This occurs when one of the smaller secondary veins is blocked.

- Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO): This occurs when the main vein of the retina is blocked. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion has more severe consequences than branch vein occlusion, which only affects a portion of the retina.

Among the most common causes, there are vascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, an increase in blood lipid (fat) levels, diabetes, smoking, overweight, and also elevated eye pressure (glaucoma). Sleep apnea is also a frequently encountered contributing factor.

The progression of central retinal vein occlusion can vary significantly. There is a possibility of complete or near-complete recovery in about 20% of cases, while on the other hand, there is a risk of a major decline in vision.

The duration of the evolution of central retinal vein occlusion can range from a few weeks in the most favorable cases to becoming chronic in cases of slow and progressive worsening.

Diagnosis and Progression:

If retinal vein occlusion is suspected upon fundus examination, it is very useful to confirm the diagnosis with fluorescein angiography, which clearly shows blood circulation in the retinal vessels and analyzes its consequences. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides valuable information for assessing macular edema, which is a very common consequence of vein occlusions.